I am humbled by the response to my request for insight into what my next project, my legacy project, would be. Thank you to those of you who responded within Substack or engaged by email. Thank you to those who pledged subscriptions and those who suggested different ideas. Thank you to those who urged caution, knowing the burden such an undertaking might become. Thank you to those whose enthusiasm was inspiring.

When I tallied your responses, it was a dead heat between revisiting With or Without God and digging into the heresy-trial-that-masqueraded-as-a-fitness-for-ministry-review. Some urged a combo product which was also a possibility. As a result of the enthusiasm for both topics, I began configuring a project that would be able to use both the book and the trial proceedings, weaving pertinent bits of the transcript of the trial in with segments of the book.

Win/Win, right?

Wrong. I was totally unprepared for the emotional reality.

Some of you had gently questioned the wisdom of revisiting the heresy trial, noting that it might be emotionally disturbing. You were right. Reading With or Without God, however, was also a challenge. I decided I needed to step back and rethink. Thank you for your wisdom and your patience!

So.

Here’s what happened. Long ago and right now.

With or Without God

Bishop John Shelby Spong, at lunch one day, introduced me to his HarperCollins publisher, David Kent, and told him that I was a writer. I’d never written anything longer than a university essay in my life (and that was back in the days when, if you wrote very well - I’m talking penmanship - you didn’t even have to type it).

As they say, the rest is history. I did write a book and I dedicated it to Jack, noting that he deserved all the credit but none of the blame. He was an amazing mentor and I miss him deeply.

Once I was through the editing process for With or Without God (WoWG), in early 2008, I never really picked the book up again; at least not to read it. Rarely, someone would ask me to read an excerpt, but by rarely, I mean, maybe twice. In truth, maybe once. I just didn’t read it again. One embarrassing bit of evidence to that fact, which I may have shared before, was when a young man approached and said something to me. I was impressed with his thinking and erudition and responded enthusiastically. Here was a guy who “got” what I was trying to do, so I said something like, “That’s brilliant!” He looked at me oddly and said, “It’s from your book.” O M Goodness. So so so so so so so so so so so so so embarrassing. I could have died.

But as I began to engage with WoWG for this podcasting project, I was reminded of what it really was and remains: a head on collision with the broader church that had skid marks going straight back to my childhood.

The church across the street

In Sunday School at my growing-up-church-across-the-street, Sydenham Street United in Kingston, ON, my entire Christian education was guided by The New Curriculum. It was a controversial Sunday school program based on contemporary biblical and theological study. I’m one of a thin slice of Canadians who were offered its treasures because it only survived the years between my kindergarten class and my confirmation. But it taught me the Christian story I embraced as a child and which, the most part, I still carry within me.

But I was a kid, obviously. I didn’t know we were using a curriculum that made people so angry they were marching on Church House. I didn’t know we were studying contemporary biblical scholarship, and that objection to the project would end a longstanding cooperation between Baptist and United Church publishing houses. I didn’t know that those who wrote books for the The New Curriculum, would be castigated by members who were shocked to find that contemporary scholars didn’t believe, literally, in every word in the Bible. Donald Mathers, who would later become Principal of Queen’s Theological College, authored the first book in the curriculum to be printed, the adult study book titled The Word and the Way. He was abysmally treated by those in the pews who were not interested in leaving behind their god-in-the-sky and that god’s miracle-wielding son. It was the ongoing story of resistance to change, made more vicious by those who believed the church should remain the same throughout history, and it reared its old and ugly head in those years when change was emerging and hope was but a flickering flame1 .

But I didn’t know that then. I was just a kid learning about a nice man called Jesus, and his father, God, who cheered him on, and when we thought about him, would cheer us on as well.2

Education

When I arrived at Queen’s Theological College, a direct result of my Sunday School years’ adventure with The New Curriculum, my theology, Christology, and understanding of the the Bible was already dramatically different from many, if not most, of my fellow students. I had no idea that many members of the UCC remained oblivious to the teachings of The New Curriculum; the arguments that had taken place twenty some years before had fizzled its influence. So professors gently prodded and teased all of us toward contemporary understandings and the latest theological and biblical scholarship.

That exploration was engaging and exciting, but I’d been prepared for it. Some students hadn’t. Their trepidation regarding critical examination of the Bible, however, wasn’t really an issue; there will always be professors happy to support their students’ learning even if it doesn’t cross the line into “The Bible wasn’t written by God” or “Jesus isn’t coming back”. Many of those students were ordained and stepped into the clergy role of preaching solid and comforting theology that kept Jesus risen and in heaven and God taking care of everything else. I just wasn’t one of them.

Having been found “Suitable for ministry” by Kingston Presbytery, I was ordained in 1993 while serving at St. Matthew’s United Church in Toronto.

Seriously??? This is what people really believe???

My time at theological college long behind me, my frustration with the wider church grew. Indeed, it often stunned me as my theological worldview came up against the theological worldview of many of my colleagues. They certainly didn’t match the contemporary biblical or theological scholarship I’d revelled in at Queen’s. I found the social justice commitment embedded in me by my Sunday School curriculum - to love others meant to care for and help them, too - and reinforced my theological education often wasn’t the core reason my colleagues climbed into their pulpits every Sunday. Regularly, when I shared my own belief system, or the actions I believed were demanded by it, I’d come up against thinking of the previous century or earlier. Few were those who felt the same way about ministry as did I, and I cherished their companionship, encouragement, and friendship along the way.

Rather than let the ideas and ideals of the Christianity I knew and loved be lost, I and several others committed to the work of promoting them. With the encouragement of Jim Adams, founder and leader of The Center for Progressive Christianity in the United States we founded the Canadian Centre for Progressive Christianity (CCPC). James Rowe Adams - his full name - was a huge figure in my life at that time and whenever I drive past a street in my town with the name James Rowe, I remember his kindness and guidance.

It was at the launch of the CCPC in 2004 that I first met Jack and Christine Spong. Jack gave the keynote address. And, of course, like millions of others, I fell in love with him.

Over the next couple of years, I became recognized as a leader in the progressive Christian community. Many were embracing what we were doing. Many were excited by the idea that church could and should focus less on biblical arguments and Bible study and more on what the Bible might inspire within us toward the work of creating a better world. But little was changing in the churches they attended. Services remained the same. Progressive voices were being ignored. Church was hard for those whose engagement the CCPC inspired. I wasn’t the only one frustrated.

Back to the Book

By the time David Kent slid his business card across that restaurant table, I was ready to take up the challenge and With or Without God: Why the Way We Live is More Important that What We Believe was my response.

Which is why it is a rant. It came from a place of deep frustration with the church and its refusal to share the message that I, and thousands before me, around me, and still to come will forever interpret as the message of the Gospel: If you can do but one thing, let it be this: love one another. Not that you should learn to read the text in its original languages. Not that you should pore over ancient verses looking for contemporary meanings. Not to spend years of your life listening to exegetical sermons explaining long lost original meanings. Not to be forced to believe that a concept is a being called God and that the concept called God had a child that died for you so now you’re safe while before you weren’t but were blissfully unaware in your ignorance.

With or Without God poured out of me. Like liquid frustration it poured out onto paper, into print, and on out into the world.

Big sigh. That felt good.

And it had.

But revisiting that frustration maybe isn’t the right thing to work on now. Indeed, I don’t think it is.

The Heresy Trial

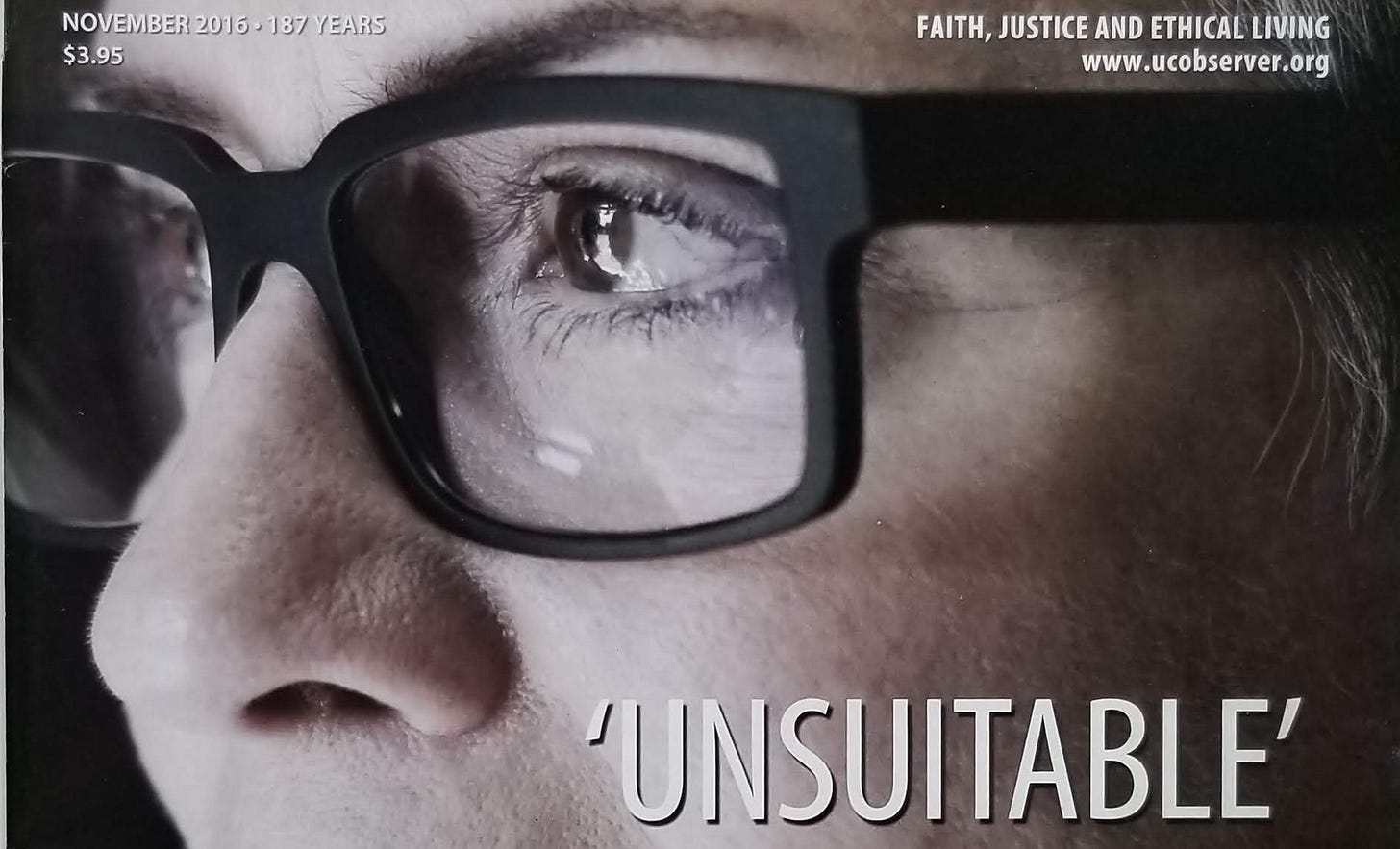

A few nights ago, sitting in a small house in Nova Scotia, I began reading the transcript of Toronto Conference’s review of my effectiveness. The review had been set up by David Allen, then Executive Secretary of then Toronto Conference. Not requiring that a complaint have been made against me, in 2014, Allen took a motion to the Sub-Executive of Toronto Conference requesting a review of the effectiveness of my ministry and based on my unorthodox beliefs.

There had been no provision for such thing in the United Church. Reviews of effectiveness happened with limited regularly. They were undertaken for situations in which complaints have been made against clergy by members of their community or beyond. Those complaints generally involved inappropriate sexual behaviour, embezzlement, or abuse. I know of situations where colleagues were reviewed for their effectiveness when conflict was rampant in their congregation. But a review of effectiveness doesn’t strip someone of their ordination rights or automatically remove them from ministry; there was no way to unordain a minister. And there had certainly not been a review of a clergy person’s theological beliefs before. It was new territory for the church and, as such, required provisions.

The cooking of provisions

Allen, in search of the provisions he required to review me, consulted the United Church’s General Secretary, Nora Sanders. Sanders served as the highest administrative official in the church but had no theological training. Between them, they came up with a ruling that brought used existing interview regimens to create the process they needed.

Candidates for ministry undergo a process of interviews to determine if they are suitable for ministry. If they are found suitable, they are ordained and called to serve in a pastoral charge or other form of ministry within the church. If they are found unsuitable, they are barred from leading in ministry roles in the church.

Sanders jiggled things around a bit, and presto, a new disciplinary process was created for clergy already ordained. She ruled that the result of a review of effectiveness could be determined to result in the same finding under a review of suitability, something previously only exercised in a candidate’s process toward ordination. In a new disciplinary process, she allowed for questions of theology to be asked of ordained or commissioned ministers within a review of effectiveness.

That had never before been undertaken in a court in the UCC. If I was found to be ineffective by Toronto Conference, via Sanders’ ruling, the decision could be easily slipped over into a ruling of unsuitability which could then provide for my removal from ministry. They took a process used to ensure unsuitable candidates were never ordained, and slipped it into the process of reviewing an ordained minister for the purpose of, essentially, stripping them of their ordination rights to leadership in the church. And that gave Allen the tool he needed to remove me from ministry in The United Church of Canada.

And, surprise, surprise, I was found to be ineffective because of my beliefs. By way of that decision, I was found to be unsuitable. But, there, they hesitated. I was not removed from my congregation. They “allowed” me stay but I was not permitted to go to any other congregation without their leave. Like I’d want to.

Interestingly, since my trial, no other clergy person previously tested for suitability through the very ordinary ordination process has been retested for suitability subsequent to their ordination. I may have been the very first and the very last subject of a heresy trial in The United Church of Canada. I guess that’s something.

The first two questions

I hauled out the transcript of my hearing in order to determine how to go about integrating it with With or Without God. Like the book, I hadn’t looked at it since the trial so sliding my eyes across the words was like going back into a time I had remembered only vaguely as one of the most stressful in my life. And what I found was fodder for more stress.

Rather than basic the questions on A Song of Faith, the denomination’s 2006 statement of faith which had been written to provide ample room for a variety of beliefs within the denomination, the questions referred to the entirety of the United Church’s doctrine.

The first question was pretty straightforward and asked me what ordination meant to me. “My ordination is the fulfillment of several years of exploration and study which … invited me to offer and acknowledged my ability to offer my skills and gifts to the United Church of Canada to use in a leadership position within their congregations.”

Maybe that was a trick question. Maybe it was really about the spirit of God descending upon my shoulders as a white dove. If it was, I blew it right out of the gate.

The second question wasn’t asked of me. I can still remember its presentation: it was spat at me. “From your understanding of the United Church of Canada’s doctrine and beliefs what do you not accept?”

Now, this interview, given the whole “suitability” nature of it, should have looked, smelled, and wagged its tail something like the interview a candidate for ordination would have experienced. No candidate in the history of the United Church would have been asked to know ALLLLLL the doctrine of the United Church sufficiently to be able to comfortably tell a team interviewing them what they didn’t accept. And what candidate would want to start with what they didn’t believe? It was absurd. I stumbled. My lawyer objected. The question was refined. The interviewer backed down and asked me to name the top three beliefs of the church that I rejected. I probably did a little choking thing at that point, but, for the second time, refused the question as absurd impossible to answer. It was withdrawn.

And so the process went. From one absurdity to another.

I had to stop reading somewhere on page four.

After that, I didn’t sleep most of the night, furious at the unjust process. I was furious at the three years of stress endured under the weight of the review and the legal time and cost required to defend myself against their accusations. Furious at the ludicrous interference with the rich and vibrant ministry I had with my congregation and was sharing through my writing and the privilege of speaking in places all around the world. And furious at the blight placed upon The United Church of Canada, a denomination I loved and had committed my life to, a blight created and perpetrated by small-minded, mean-spirited administrators who lacked any creativity other than that required to manufacture problems where they didn’t exist and who intentionally created a process to undermine a vibrant and meaningful ministry.

Undermine it, they might be able to do. But they couldn’t destroy West Hill’s ministry. And they couldn’t upend my leadership. They did manage to compromise some of the most productive years of my ministry, however. And they did invite my colleagues to revile me, something many of them did with relish and not only aiming their ire at me, but also at members of my congregation. Some of their behaviour was deplorable.

So, around 4:00 that morning I decided that I wasn’t going there.

But I need to go somewhere.

So, here we are, starting over …

I am starting again and hope this next foray into a legacy project will be one both you and I will enjoy.

Amen

Many of you may not know of my second book, With or Without Prayer, We’re All the Answer We’ve Got. That’s probably because that HarperCollins refused to let me call it that. Too derivative, they said. Instead, they titled it Amen: What Prayer Can Mean in A World Beyond Belief.3 Seriously. You can’t believe I’d actually write a book with that title.

But it didn’t matter. The book died pretty quickly. I underwent surgery for cancer of the ovary the week after the book was published so I had to rely entirely upon my publicist’s promotion of it. Trouble was, the only previous publicity experience she had was promoting a Tragically Hip concert in Calgary! lol! She encouraged me by telling me she had a friend there who went to church. Another legitimate lol! Well, to be truthful, it was a long, deep sigh. And crickets. Crickets and crackers. No interviews. No articles. Just soft foods, a huge scar, and recovering at home.

With or Without Prayer

With or Without Prayer used the different forms of prayer that have framed Christian liturgy for centuries to explore the intuitive work that communities do when they are together. Indeed, I think the impetus behind these four forms of prayer are essential to strong human community. Though are all oriented toward God in church, most of you will recognize them even if you aren’t regular churchgoers: Adoration, Confession, Thanksgiving, and Supplication.

But if you orient these elements toward the exquisite world around us, the life it fosters, and the human family that depends upon it, they become part of our everyday responsibility and commitment to ourselves and to one another: Expressing awe and the appreciation of all life offers us; acknowledging our failures openly and honestly; celebrating the joys of life and the commitments offered to us by others; and sitting with the truth that we are all people who make mistakes and are in need, seeking support, and when we can, finding strength in sharing our embarrassment and isolation.

Isn’t that the best of what church has been?

I think I can move into that without dragging all the frustration that was so prevalent in With or Without God along with me.

The Heresy Trial Papers

When I was preparing for the review of my effectiveness, I wrote several pieces in response to the questions I was expecting them to ask. Those pieces are still meaningful to me. They were written out of my experience leading an extraordinary congregation. West Hill, despite losing well over half of its members when it refused to shut down the journey it had begun, continues to challenge the confines of traditional doctrine and language. Doing so, it made church something that maintains crucial interrelationships that, for most of our history, have been the backbone of our society. They invite people to fall in love with being together. They follow the flow brought about by recognition: I see you, whole and beautifully broken; I recognize you because I am beautiful and a slavering mess, too. By doing so, their individual lives are better and their engagement beyond their homes and families becomes a commitment to a better world. With or without Articles of Faith. With or without God. With or without assenting to an arbitrarily defined set of beliefs.

I can comfortably revisit those written pieces without having to delve into the absurdity and injustice of my heresy trial. Through them, I can bring you what I consider to be the best parts of that trial: my responses to its challenge. Those responses frame what we were doing at West Hill at the time, something that I very strongly believe is still worth doing.

It’s important to remember that West Hill did much of that work themselves. Indeed, in 2004, they wrote their first guiding document which was named VisionWorks. I was involved in that work but didn’t realize its implications until it was being presented to the congregation. The person leading the discussion noted that it didn’t profess a belief in God. I looked down at the document in my lap and quickly scanned it. Nope. No belief in God. Oh My Goodness!

That document has been rewritten every five years since. I was never again involved (and not because I missed that little bit about God; because I wasn’t needed). It continues to define the congregation and has moved it forward in every subsequent iteration. I couldn’t be more proud of the work West Hill did all those many years ago and continues to do today.

So, now this project is something I can do

Managing the preparation for this project means managing not just the files and the equipment, it means, as so many of you noted, managing my own physical health and emotional wellbeing. I was pretty enthusiastic about the first pitch, but this refined choice seems to be a far better fit for where I am and what I wish to provide. Weaving the theological commentary from my presentation to Toronto Conference into the material presented in Amen With or Without Prayer (WoWP) will be a good experience for me and, I hope, for you.

In the next few weeks, I’ll begin the work of recording the parts of WoWP and reviewing the pieces I had prepped for Toronto Conference. Together, they will invite the inclusion of liturgy, materials I’ve written to support gatherings at West Hill and elsewhere, and those collected for a liturgy project that has been sitting on my computer gaining whatever sorts of dust accumulate in our digital worlds.

I don’t know about you, but this reorientation has me feeling enthusiastic for the work. And that can only be a good thing.

Thank you for being with me. Truly.

Into the hallowed curve of each other’s hearts,

we lay our stories

the beautiful and the ravaged,

the brightly coloured moments

of joy,

struggle,

engagement,

and hope,

and the dull landscapes

of the boring,

the exhausted

the tedium of the day to day.

and in so doing

invite one another's hearts to make holy

the detritus of our lives.

And isn’t that exactly

what we are here to do

for one another...

For our only selves.

June 17, 2025

© 2025 gretta vosper

P. S. If you aren’t engaged in a community of meaning where you are, I invite you to join West Hill either in their building4 or by Zoom any Sunday morning at 10:30 ET (or EDT, depending on the time of year). That’s the link to do so. I am no longer there, of course, but they have just called a new leader for their Sunday Gatherings. Joe Pettinger, a member of The Clergy Project, and perfect for the position. I am so so so pleased he is there carrying forward the project West Hill has created.

I have just read and reviewed Jim Veitch’s book on Lloyd Geering’s heresy trials in the Presbyterian Church in the 1960s and 70s. Lloyd survived his trials by departing the pulpit but the Presbyterian Church took a radical right turn as a result and never really found its way back. Lloyd is still engaging. He’s now 107, the second oldest man in New Zealand.

Yes, that is a terribly simplistic version of my Sunday School curriculum. My point is, simply, that it was about learning how to love one another and having a champion to whom you could appeal for help in that long, hard work.

If you think I would have written a book called Amen: What Prayer Can Mean in a World beyond Belief you likely haven’t read my first book. When I sell a copy of Amen, with the purchaser’s permission, I use a Sharpie to cross out the title and write With or Without Prayer, We’re All the Answer We’ve Got - the proper title - across the front of the book. Don’t tell HarperCollins.

West Hill is located in the east end of Toronto, close to the city’s limits. 62 Orchard Park Drive. It is on the corner of Orchard Park and Kingston Road, just a few blocks East of Morningside Avenue if you’re coming from the west and just inside the city if you’re coming in from the east using the Kingston Road exit from the 401.

You write with great clarity and purpose! This sounds like a project that will enthuse and fulfill. I look forward to seeing it take shape.

I love how you explain the evolution of your thinking on this as it gives context to what you’re now doing. Updates will be most welcome.

John