Nature unloosed

The gloves are off

I’m certain that scientists have done studies on the significance of trauma experienced by those who witness it secondhand - watching it on television or hearing another describe it. Maybe they’ve found that trauma only occurs if a television viewer is very young, and (presuming they are spared the news channel) doesn’t know that what they are watching is a made-up story and the people simply actors pretending to be frightened. Or, forget studying the young, maybe they’ve found that watching a Harlan Coben series is enough to frighten anyone out of their wits but not enough to cause trauma. Scientists could have started studying the question when Orson Welles had to break into his radio telling of The War of the Worlds to calm people down, tell them to return to their homes, and assure them he was reading a story; there were no Martians taking over the planet.

The reason I’m worried about trauma is that millions of us watched Los Angeles burn and continue to follow the horrific outcomes of that fire. Some of you may have had a sense of scale because of your familiarity with the city. Others have no such personal knowledge but walked the streets with newscasters who were able to point out landmarks, listened to James Woods weep when he told the story of finding his demented 94 year-old neighbour in a small room behind the kitchen when others had said the home was empty, and a photo, the next day, of the church where Jamie Lee Curtis got sober twenty-five years ago engulfed in flames, her sentiments strong for those who would have nowhere to find the support they rely upon in the aftermath of that inferno.

Can we be traumatized from such a distance? Can images we see on television, images we know are absolutely real, maybe even real-time, create the same kind of impact as if we were right there? I think they can and do create that impact and I think we can be, and are traumatized. At least, now I think we can. And that’s because before, we could tell ourselves it couldn’t happen here.

Planetary Boundaries

You see, Mother Nature’s1 been bound by planetary rules that we all know and understand according to our geographic locales. Within those rules, she could do the most ordinary and the most extraordinary things. She could grant long, even seasons in which we’re fairly good at anticipating the weather. She could shock us with wild, unexpected storms, and then take us back to whatever normal might be. She could breathe in water from the seas and carry it far over bordered lands, then send it down in little drops which, in turn, became the nectar of flowers, the sap in a tree, and the explosion of flavour released into our mouths by a raspberry. She could lift tons of sand and carry it as far as she wanted, dropping it down in a completely new configuration of hills and whorls, its creation either boon or disaster to whatever had thrived in either place. She could turn the earth beneath our feet into a stream or uproot trees with the force of her powerful winds. But all of what she did happened within the stability of Earth’s planetary boundaries. Normal would, and did, return. We built whole civilizations on “normal”.

Because we recognized Nature’s patterns, we knew when to take shelter, when to brace ourselves and what the worst might be when it did come. We recognized the changing of the seasons, planted seeds, set out on our boats, patterning our behaviours in accordance with what we had come to know. Sometimes, we died, and sometimes the world burned, but the norms would return, things balance out, and healing begin. And Mother Nature would lull us back into the normal rhythms of life.

God

In our ignorance, we believed the rules to which Nature was bound to have been laid down by gods. Over the course of human history and in every populated area of the world, there have been gods responsible for Nature - Demeter, Pachamama, Cere, and Poseidon (whose most recent undertaking was a bad 70’s disaster movie which I absolutely loved, belting out There’s Got to be a Morning After for weeks. Don’t tell anyone). In our arrogance, Christians just named their god “God”, as if there had only ever been one. The job we gave God was to protect us or teach us how to protect ourselves.

Considering ourselves the most important living beings on the planet (God wasn’t understood to live here), it made sense that all Earth’s systems were created specifically to support and nurture us (or, to be specific, we Christians). If a storm destroyed a neighbour’s lands, there was a godly good reason for it and you could pitch in and help rebuild or stand to the side and self-righteously condemn; God would support you either way. To be sure, neighbourly neighbours often pitched in regardless of their beliefs. And if you had the unbelievable luck of a whopping good crop (or twelve strong children), your efforts (or fecundity), of course, had nothing to do with it; your bounty was the result of God’s blessing which had been bestowed upon you for whatever reason you might choose to declare.

Expressing thanks

Once each year, the cadets from the Royal Military College join the congregation at Sydenham Street United Church, the limestone edifice across the street from the garden gate of my childhood home. I was always impressed on that Sunday, the church filled with young men - back then, only men were admitted to the RMC - and officers in dress uniforms. Red and gold, shining brass and leather, pillbox hats with chin-biting straps. Hundreds of them.

My father, who was involved in the leadership of the church, as many men were back then, attended the main Sunday service every week. But on Cadet Sunday, he was different. I can’t tell if my memory of him being in full naval uniform is real or if I’m imagining it, but I do remember being busting proud of him on those Sundays. I could feel how important it was to him, how proud he was of each of those young men. Maybe he was even a little envious that they were studying while, at their age, his education had been deferred by the war. Or maybe that is what made him proud. I don’t know.

On that Sunday, we would sing Eternal Father, Strong to Save,2 the Naval hymn.

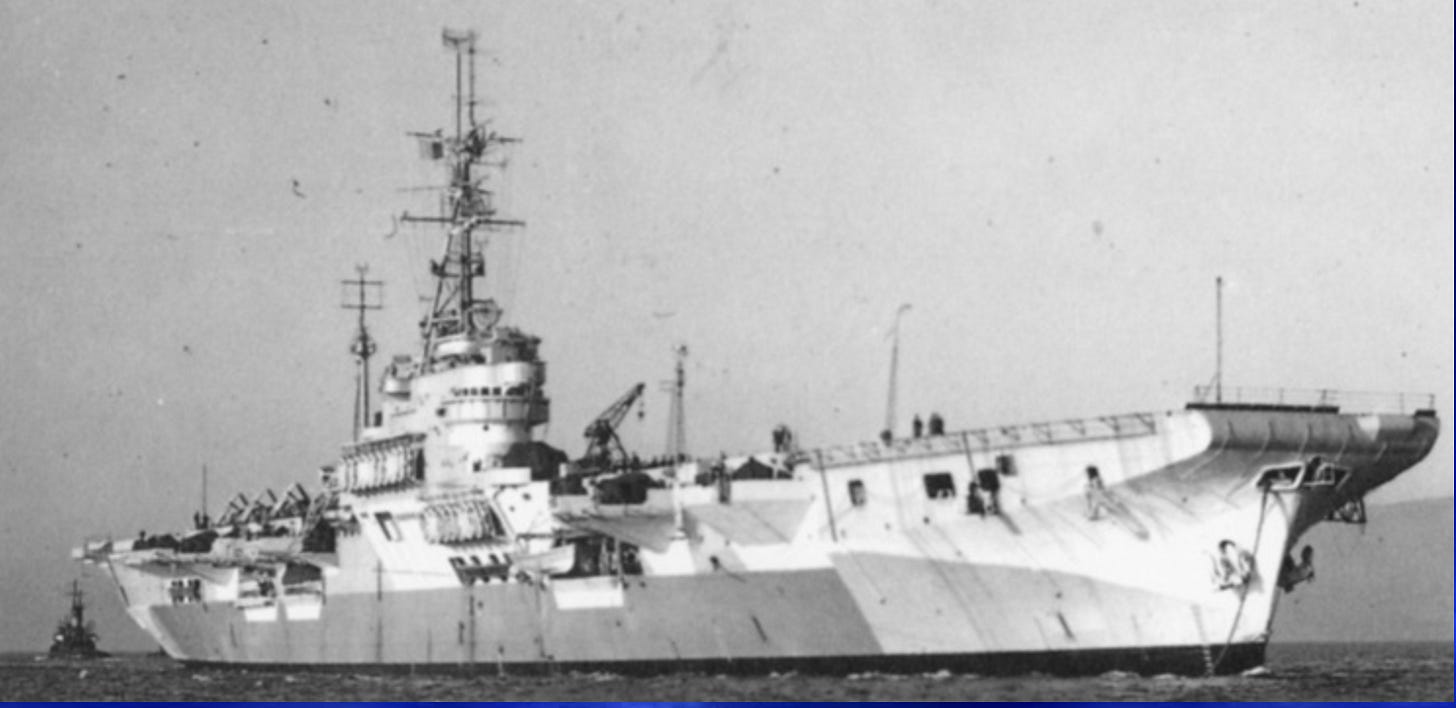

It was my dad’s favourite, one he would have sung often during the war, mostly as a seaman on the HMS Glory. Here, at home, safe and sound, with close to a thousand voices lifting the melodies of the song with him in a spectacular sanctuary built for music, accompanied by a tremendous pipe organ, he was deeply moved, his eyes watery. Indeed, my own eyes still fill with tears when I hear this particular hymn, probably from my childhood association of it, and the memories of my dad’s deep and rare emotion.

Perhaps he experienced the trauma known by every wartime recruit as he entered the Navy, refusing the sanctuary his mother had bought him in the form of a farm, leaving home along with thousands of others who had no idea what they were getting into, where they were going, or how they might die. Trauma, in such circumstances, isn’t in “reaction to”; it comes in waves of “anticipation of”. Perhaps, one way or the other, in times of war, entire generations are traumatized by those oceans of not-knowing, made up of both those who go to war and those who wait for them at home.

The hymn’s first verse lays out the entire theology of the Christian world, the belief that God, the eternal Father, takes care of us, keeps Nature bound, holds her limits, and has the power to protect us.

Eternal Father, strong to save, Whose arm does bind the restless wave, Who bids the mighty ocean deep Its own appointed limits keep; O hear us when we cry to Thee For those in peril on the sea.

The planetary boundaries I keep referencing have always been understood by the religious to be boundaries laid, kept, and defended by supernatural forces, God, by any other name. The ocean’s limits, overseen by God, would be kept and we, as a result, protected.

It was a powerful idea.

And it was so terribly, terribly, terribly wrong.

Turns out, God is no match for Nature

As it turns out, no matter how fervently we bend our knees and pray for rain, its absence has destroyed crops and bankrupt farmers. And no matter how fervently we’ll pray for it to cease, it will wash out towns, take our loved-ones, and leave the land unrecognizable. Because concepts, no matter how brilliant they may be, are no match for Nature’s raw realities.

For the very few millions of years we have sought to live in harmony with Nature, our greatest task has been trying to figure out what the hell she was doing at any given time in any given place. We have wanted to know what we could expect, and how to survive. We humoured ourselves with idea that prayer would save us and explained away every time it didn’t. But Nature is the reality with which we are in relationship, with or without belief in gods. And for the most of our history, she’s played a pretty steady game.

On some rocky socket

Trouble is, lately we’ve been f*cking with her. It hasn’t been long, the worst only in the last thirty years. But it has been long enough that the rules of engagement changed. It’s a “No holds barred” scenario, the rules by which we and Nature have always played no longer applicable. Indeed, we’re struggling to decide if there are any discernible rules emerging, so chaotic are the weather patterns we are seeing. Is the North Atlantic Current, which is responsible for Europe’s mostly temperate climate, going to hold or will it reverse? If it does, what will happen then? Whatever happens, it most assuredly is going to happen here sometime. “Here” being wherever you happen to be. It’s coming. Whether it is weather itself destroying our homes and communities, or the results of weather taking out the food supplies that land on our plates from thousands of miles away or those transport corridors themselves. It will come. And the trauma is coming right along with it. We’re all ending up “on some rocky socket.”3

Nature is experiencing a new, irrepressible freedom. At some point in the future, things may stabilize, but that future may be a long way away. With temperatures continuing to rise and a lack of agreement about how high they might go, it may be centuries before a truly stable climate is, again, achieved.

Did you know that most of the world’s bergamot has thrived along a 90 km strip of the Ionian coast for as long as anyone can remember because there, in that little place, Nature has protected and provided for the miracle that is the Bergamot tree? Imagine that.

I wonder where will it grow in 100 years?

We are our own disaster

The lyrics to Eternal Father are powerful. They not only articulate our beliefs, they outline the arrogance within them. Imagine our believing that the god called God was willfully keeping the oceans within limits that would protect us! First off, the evidence didn’t even support that theory! The deity was well known for the frequency with which it had wreaked havoc on the shores of the world. The evidence that God refused to hold the waters back, grounded in the belief that he could do so and had refused, often resulted in our searching our own souls for some horrid thing we’d done to cause God’s fury. Or maybe we searched for some other poor bloke and blamed them for bringing tragedy to the community. That, too, is an ancient story. But we had to do that because we believed we were under God’s protection. And many still do believe that, despite what is happening with sea rise and floods, wildfires, droughts, and the storms we are witnessing on a too too regular basis. You know this. I don’t have to draw this out any longer than it need be.

Back to Dad and the Naval Hymn

As a result of my indignation at the hymn’s arrogance and because of the love I have for the memory of my father and the power of the music, the last time I heard Eternal Father, Strong to Save I decided to write new words for the tune. For my dad. He died over 15 years ago so I don’t have to worry about what he would have thought about my tampering with it. We’d have had a good discussion about it; ultimately he’d have come down on my side. He was a genius, albeit a troubled one, and his assessment of scientific reality was always spot on so he’d have seen the insanity in the traditional words even if he’d found it hard to let them go.

When I began writing, I wanted to address that sense of privilege the song assumed we deserved. We, the world’s most self-aware species (that we know of), still forge on into the future at breakneck speed, our own self-made destruction sitting square in the middle of the road in front of us. A ways back, we might have been able to turn off on another road, or even swerve, hit the ditch and graze on past, the scars to prove it crossing a variety of continents. But not now. Not now that the founder of the feast, Nature, herself, runs crazed, on a glorious rant all her own. Not without a global effort that I don’t see materializing. Not with what’s happening in America right now, and I don’t mean weather events.

There is a traumatic response that legitimately arises when the reality of what is unfolding around us hits us square in the chest with stunning force. It hit me when my son was born in 1991 and I was already afraid for his future. It sent me reeling when I read Alan Weisman’s exquisite The World Without Us back in 2007, wanting, as we all do, to keep the beauty surrounding us, even that which we have created, and find ways to ensure it will last. It hit me when my first grandchild was born because I had long acknowledged what the world would be like when they attained the age I was at the time.

Forward, Fearful; Forward, Fearless

The message I want to imbue, however, is not lament or shame or sadness. Whatever happens in the next several decades, the world will carry on with or without us, spinning its perfect, brilliant blue orb along its ancient course. That is reason enough to be grateful. Our responsibility in the face of that is to live into dignity, into responsibility, into caring for one another and the living world to the absolute best of our abilities. It is to hold ourselves together, to hold one another, to live through the trauma toward love, understanding, courage. Live toward one another as best we are able.

With or without us, the clouds will gather, the rain will fall, the water will flow, and the seeds will split, releasing their ancient story into the mud. And life will go on.

With us or without us, can you not imagine just how unbelievably wondrous that will be?

Beyond the Epochs

Tune: Melita

The morning breaks and casts its dew

as clouds drift o’er a brilliant blue.

Young forests green the blackened scars

that might, one day, tell who we were.

The world we know will change and thrive

beyond the epochs we survived.

Through sunlit days and darkened nights

we spend the moments of our lives

creating beauty, mourning loss,

the joys of love yet bear love’s cost.

The world we know will spin beyond

the days we dance and sing our songs.

Earth’s story, woven long before

our first ancestors crawled ashore,

continues and will long whirl past

the crumbling of its mountains vast.

The world we know will long outrun

the days we circle ‘round the sun.

Our gods, we thought, could rule the waves,

and all our joys and blessings save.

Too late we learned the oceans deep

required that we, our limits keep.

Still, after all our words are gone

the winds and tides will raise their song.

gretta vosper

© 2025 Gretta VosperI hope Chris Fleischer’s gift of the music “Melita” allows you to sing along. And I hope you find a fluency of hope as you sing.

I’ve intentionally chosen to use “Mother” as a descriptor for nature and Nature with personified, feminine characteristics. We live within the womb that is the world’s environment and we are entirely dependent upon nature for our lives, our sustenance, our future. Seems a very female-oriented relationship so I’ve run with it.

Do check out that link; the congregational singing is lovely. And feel free to join in with them! No one is watching!

Live toward one another…❤️

Thanks for this reflection and the new lyrics. I believe that it is so important to foster hope in these insane times of such mass destruction, and for me that is difficult. Your reflection reminds me that nature is clearly demonstrating that our relationship is fractured. We only need to hear.